Joy and Resistance Bloom in Medellín

Elaborate flower arrangements, known as silletas, are displayed throughout Medellín and beyond during the Flower Festival. This one was found in the nearby town of Guatapé.

By Opal Amon-Lucas

Medellín, Colombia

Feria de las Flores, Medellín, Colombia’s annual flower festival, has little to do with flowers to me, and everything to do with the restoration of political and societal peace. After spending six weeks in an academic program in Cartagena, Colombia, living with a host family and attending classes on the political history of the country, I finally began my solo travel in the City of Eternal Spring.

The Medellín Flower Festival is an annual celebration that began in 1957 in the Colombian department of Antioquia, a region of the country known for coffee and flower production, as well as the center of cocaine cartels and the associated violence in the 1980s and ‘90s. Over the course of ten days every August, displays, parades, musical performances, and events materialize all over the city, honoring one of the most important, and joyous, exports of the region.

Visiting Medellín during the festival is like being on a scavenger hunt scattered all over town. Everywhere you turn, stores display huge flower arrangements, known as silletas, in front of their shops. These exquisite floral creations showcase handmade designs and slogans from artists honing a long-practiced tradition of bending petals into art.

Many events throughout the festival are suggested only for tourists or specifically for locals, but the closing ceremony brings together hundreds of thousands of people from around the country and the world. On the final day of the festival, I stood shoulder-to-shoulder in a crowd to watch the closing ceremony. After a brief but intense summer downpour, the festivities began.

The closing ceremony of Medellín’s Flower Festival. Individuals known as “silleteros” carry floral displays (silletas) on their backs as they parade down the street.

First up was a marching band comprised of xylophone players and drummers in all black outfits with large green sashes. This was followed by the classic car show where the drivers, typically elderly Paisa women, throw flowers into the crowd to roaring support. (Paisas are people from Medellín and the surrounding Antioquia region.) The crowd showered the most charismatic women with ebullient cheers of “Abuela! Abuela! Abuela!” The cars were followed by dancers and then the main event, the procession of silletas—the ornate flower arrangements—which are built into wooden frames that are worn like a backpack.

Every silleta was as intricate as a pointillism painting, made not of paint dots, but flower petals. Dried, dyed, cut, and woven, each artisan had taken the time to make not just a flower collage about their Colombian heritage but also made from their heritage. I wanted to reach out and run my hand over the works, to feel the imagined scratchiness and disrupt the intricate placement. Just as paintings in a museum are framed, every silleta was bordered with a beautiful frame of flowers.

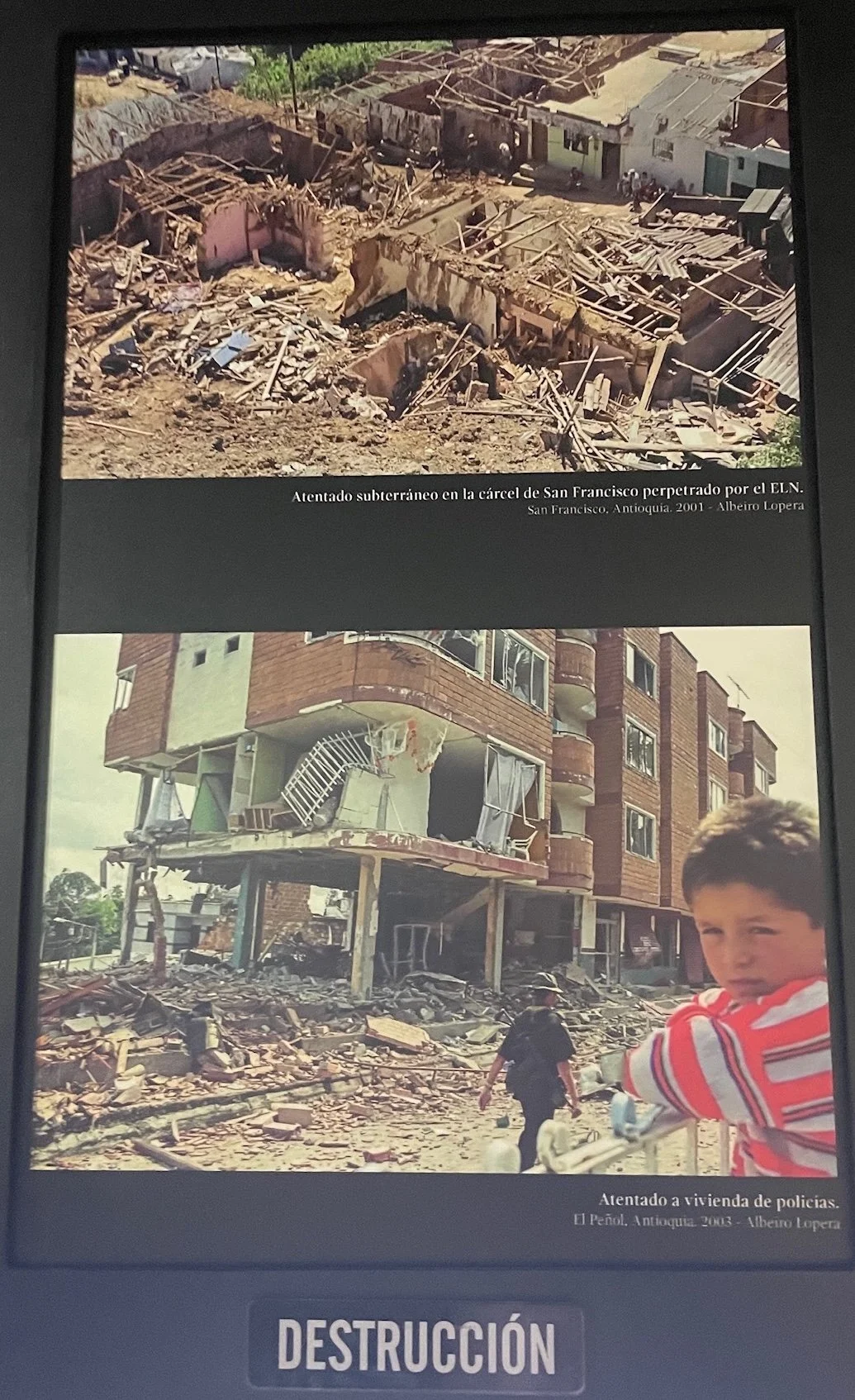

As I watched the procession, I couldn’t help but juxtapose the experience with my visit to El Museo Casa de la Memoria (the House of Memory Museum) the day before. The museum is one of, if not the, most important in the country. It tells the story of the Colombian armed conflict through open dialogue and the collective memories of survivors. Through archival photos and newspaper articles, video interviews, carefully annotated maps and documents, and stunning installation art, the museum counters the dark tourism of a city tainted by memorialization of the famous Medellín drug lord whose name local people refuse to say even though it’s plastered on t-shirts that are sold on most street corners in the touristy part of town.

An exhibit at the House of Memory that depicts Medellín amidst the paramilitary violence that continued in the city even after the drug cartels were officially dismantled in the ‘90s.

Giving voice to the victims, the House of Memory recounts what took place within the city and nation through interviews with harmed and displaced people. Medellín, maybe the rawest part of the country, still reeling, is so open about the conflict that twenty minutes after I landed in the city, my Uber driver confided in me that his mom had been murdered during the era of violence. At the museum, I heard many similar stories, making what I’d studied in a university classroom in Cartagena suddenly so real, it hung in the air of the car I sat in.

This wall at the House of Memory pays tribute to the victims of forced displacement during the drug wars—particularly to the women who rebuilt homes and lives that were destroyed.

Standing amidst the festival crowd, I thought about Medellin’s brutal history as I watched people exuberantly cheer, excited for every car and dancer that promenaded down the street; enthralled with every unique style of face paint and every clown walking on stilts; singing together songs I presume were learned in childhood and rehearsed in elementary schoolyards. The voices of local people rose together with tourists, who did not know the words but just felt grateful to be included, grateful to watch.

A silletero carries a huge silleta on his back at the Flower Festival. Each silleta has a built-in wooden frame and base so it can be transported this way or set down and displayed.

The museum and the Flower Festival paralleled what I already knew to be true: Colombia is a nation of living contradictions.

The songs, the dances, the rituals, the flowers, which for five decades have persisted through immense devastation and grief, are the collective resistance of people still alive, still breathing, still there. The resilience of the Colombian people, as they parade in the streets, in contrast to the museum exhibiting the history of violence and state-sanctioned dismemberment of bodies, cultures, and identities—felt interconnected: a conversation happening that together everyone held in a collective memory.

As I admired the strength of those marching in the parade, and thought about the many campesinos (peasant farmers) who grew and tended the flowers but were unable to join in the festivities, I felt a lifting of the past violence that weighed on every person’s shoulders. I found myself crying as the rain began again. Could this mean there is hope for the conflicts in the world that are still ongoing?

A silleta, bursting with blooms.

Opal and Nobel Prize-winning author Gabriel García Márquez in Cartagena, where Opal studied Colombian political history and Spanish before traveling to Medellín.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Opal Amon-Lucas, who grew up in Brooklyn, NY and Seattle, WA, is a sophomore at Smith College studying government and comparative politics. Opal spent eight-and-a-half weeks in Colombia last summer where she studied Colombian political history and Spanish in Cartagena and then traveled to Santa Marta, Barranquilla, Medellín and Bogotá.

A passionate advocate for budget solo female travel, Opal spent her summer after high school backpacking through Central America. She traveled from Mexico City to Guatemala, down through El Salvador and Nicaragua, on to San Jose, Costa Rica—making international friends along the way.

Where next? “I want to see ALL OF South America and the Caribbean! Eyes on Peru, Bolivia, and Argentina especially!” Opal says.

* All photographs by Opal Amon-Lucas

Published October 31, 2024